Netflix launches new docuseries ‘Conversations with A Killer: The Son of Sam Tapes’

Recently surfaced audio recordings from the prison of infamous murderer David Berkowitz disclose unnerving insights about the notorious ‘Son of Sam.’ An objective of Oscar-nominated director Joe Berlinger was to delve into the twisted psyche of a man who, despite his nurturing upbringing, conducted a reign of terror across New York City.

Berlinger’s latest endeavor, a compelling, true-crime docuseries on Netflix titled ‘Conversations with a Killer: The Son of Sam Tapes,’ is centered around the newly-discovered audio conversations between Berkowitz and crime journalist Jack Jones. These dialogues dated back to 1980 and took place in the notorious Attica Correctional Facility, an environment that further accents the terrifying nature of their content.

The tri-part series also sheds light on a telephonic interaction the director had with Berkowitz, who, at 72, continues to serve multiple life sentences for his brutal killings. ‘David Berkowitz exhibits distinctive traits compared to most serial killers,’ Berlinger noted in his analysis, ‘His detachment is what makes him peculiar; his anger and isolation were his sole motives for murder.’

Contrasting Berkowitz with other notorious murderers like Ted Bundy, John Wayne Gacy, and Jeffrey Dahmer, Berlinger highlights their relative need for an intimate, personal connection to their victims. ‘For Bundy and Gacy, the act of murder was a source of perverse pleasure. Dahmer’s sickness, meanwhile, evolved to the ultimate invasion of personal boundaries – the consumption of human flesh. Berkowitz, however, lusted for the thrill of appeasing his inner rage.’

During the mid-70s terror spree, Berkowitz, then a postal worker, paralyzed New York City with fear through a series of shootings using a .44-caliber revolver, murdering six people and injuring seven. His predatory focus seemed to be on young women with long brown hair and couples seeking solitude in lover’s lanes.

Reacting to the horrific shootings, the New York Police Department put together a specialized task force to hunt down the elusive killer. Fear-stricken women resorted to drastic measures, altering their appearances by cutting their hair or dying it blonde, while others ensured they were home-bound before dusk settled.

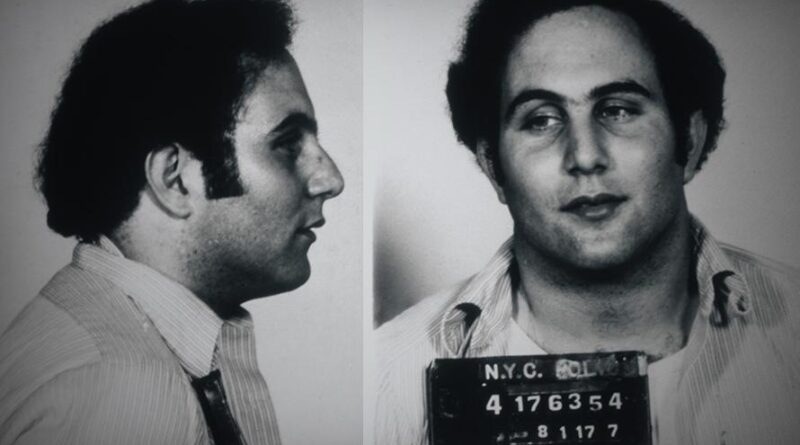

Adding a layer of terror, Berkowitz sent chilling letters to the police and the media, symbolically dubbing himself the ‘Son of Sam.’ His writings claimed that a neighbor’s dog, possessed by demons, was instructing him to carry out the murders. The city’s nightmare ceased with his capture on August 10, 1977.

Berlinger shared an interesting fact, revealing that the number of newspaper copies sold the day Berkowitz was apprehended outnumbered those sold when President John F. Kennedy was assassinated. ‘Many still propagate the idea of multiple Sons of Sams being part of a larger satanic cult. It’s nonsense, but it gave me more incentive to narrate this factual story. Simple common sense dictates that the murders ceased with Berkowitz’s arrest; if there was a broad-based satanic cult involved, why did the killings stop?’

The docuseries touches upon Berkowitz’s background; born to Jewish parents in the Bronx, he was deeply affected by the discovery of his adoption and the death of his adoptive mother due to cancer. His stint at the army in 1971 marked his rise as an exceptional marksman as portrayed in the series. However, post his military service, his mental health took a turn for the worse, culminating in a diagnosis of paranoid schizophrenia.

Berlinger argues against attributing Berkowitz’s actions to a troubled childhood. ‘There’s no evidence of a turbulent upbringing; the discovery of his adoption shook him. I don’t equate my challenging childhood experience to harboring violent rage. Some individuals weather traumatic early life experiences and emerge stronger, while others turn to horrific acts. Berkowitz, it seems, was overwhelmed by feelings of alienation and disconnection.’

Berlinger further elaborated on the psychological deviations of killers who savored their victims’ dying moments or indulged in cannibalistic tendencies. ‘While such extreme disturbing behaviors exist, they’re not common. However, the prevalence of anger, disconnection, and lack of fulfillment amongst young men in our society today is quite disconcerting.’

He went on to express his concern over instances of preventable violent outbreaks, like school shootings, suggesting that an early intervention could potentially alter their outcomes. ‘It’s bone-chilling, realizing that the story could have unfolded differently had Berkowitz received help when he needed it.’

Berlinger aired his thoughts on the current mental health crisis in the nation. ‘An alarming number of youth, especially young men, feel disconnected and lost. It’s a matter of grave concern,” he stated. In the docuseries, touching interviews with detectives, journalists, loved ones, survivors, and others close to the case are also featured.

The inclusion of the victims’ perspectives was important to Berlinger, who emphasized the need to share their viewpoint in the docuseries. ‘Engaging with victims or receiving their blessings is integral. There have been instances where I chose to cancel projects out of respect for the victims who felt they would be hurt by the broadcast. The survivors’ recollections were heartrending — their youthful aspirations brutally cut short by random violence.’

When asked what advice he would give to his younger self, Berkowitz’s response, as recalled by Berlinger, was, ‘Flee, seek help. I had the option to talk to my father.’ This resonated with Berlinger on a deep level. He implored, ‘If you’re dealing with rage, feel disconnected, or are troubled by this kind of fury daily, seek help.’