‘Gin Lane’: Hogarth’s Eerie Depiction of 18th Century Draught

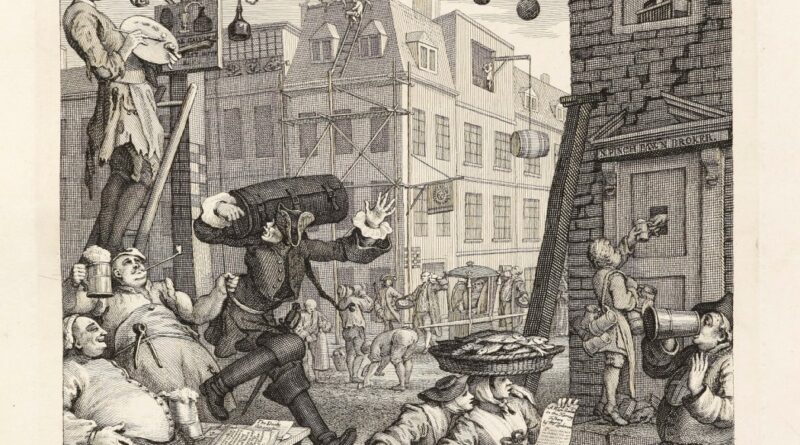

In the mid-18th century, esteemed British artist William Hogarth painted an eerie representation of the London slum, St Giles, in his piece ‘Gin Lane’. It envisions a fictitious street wherein gin wreaks havoc on its denizens, stripping them of coherence, funds, and in some cases, their very lives. An ominous visual narrative unfolds on a set of stairs, effectively displaying the gin drinker’s progression from respectability towards the abyss of mortality. The noticeable church spire provides the backdrop to this disturbing scenario, underscoring the stark contrast between faith and debauchery.

The unfolding narrative atop the stairs is unforgettable. People from all walks of life are depicted pawning their belongings at the affluent pawnbroker’s shop, a dismal testament to gin’s wreckage on industry. A carpenter parts with his saw, symbolizing how gin dismantles even the most robust of workforces. Immediately below on this stairway of despair, a mother consumed by intoxication loses hold of her child in her haste to indulge in snuff, resulting in a deadly fall that captures the viewer’s eye.

The imagery of this heavily intoxicated mother, who inadvertently becomes the murderer of her own child, symbolizes the extent to which gin can sever our most cherished relationships and obliterate familial responsibilities. Lower on the stairs, one can see a man so ravaged by gin consumption that he appears skeletal, his death seemingly imminent. His frailty is highlighted by his inability to grasp his own glass of gin, indicating that he is at the final stage of this horrific descent.

‘Gin Lane’ is part of a pair of contrasting portrayals by Hogarth, illustrating how beverage choices decisively influence the destiny of London’s inhabitants. Its counterpart, ‘Beer Street’ (also 1751), portrays the contrastingly jovial image of craftspeople enjoying a frothy beer during their hard-working day. The scene is bustling with characters like the blacksmith and a paviour in the forefront, and a sedan chair bearer satiating his thirst at a distance. Beer Street becomes a tableau of industrious London, where people drink without their efforts being significantly disrupted.

On the higher parts of ‘Beer Street’, people are seen relaxing, sharing beer from a communal jug and being toasted to by a tailor from a nearby window. They are all prospering, with the pawnbroker’s shop, the only sign of economic struggle, being ignored and left in ruins. Offering two sharp contrasting visions of London life, Hogarth delivers an insightful commentary on the perils of vice through ‘Gin Lane’.

However, ‘Gin Lane’ comments not only on societal degradation due to alcoholism but also provides an insight into an emerging business in 18th-century London — the blooming funeral trade. Caught in the corner of the viewer’s eye just above the inebriated mother lie two coffins, one receiving a lifeless body, the other conspicuously hung outside an undertaker’s shop, adding another dimension to this visual narrative.

The coffin hanging outside the undertaker’s shop was a common sight in the mid-to-late 18th century, symbolizing a thriving trade — funeral services. The undertakers were generally artisans or merchants who augmented their established businesses to include funeral services. These new participants in the funeral business were essentially intermediaries who procured different items necessary for a funeral either from their own supply or from external sources.

Consider a carpenter turned undertaker who might build a coffin himself but would need to acquire other essentials such as ironmongery, drapery, and painting work from different suppliers. This additional stream of business attracted people to take up the title of ‘undertaker’ and the more successful amongst them slowly specialized in providing funerary services entirely.

Towards the end of the 17th century, the pioneer undertakers found their niche in organizing opulent funerals for the elite, having earlier supplied requisite goods for these ceremonies. As this trade gained momentum and expanded, its growth was fueled by a profit-oriented perspective and urban centers became its focal points given the higher number of potential clients.

Hogarth places an undertaker’s shop right in the middle of the fictional ‘Gin Lane’, signifying an increased prevalence of undertaker-led funerals, which were no longer limited to the elite and had started to manifest on London’s streets. By the mid-18th century, such funerals becoming a common spectacle, making the journey from the bereaved households to the parish churches.

However, this emergent industry faced criticism. In 1699, author Thomas Tryon raised objections against undertakers claiming that they reduce the value of the elite’s funerary customs. Moreover, critics deemed the gin-drinking poor as the least deserving of such funeral spectacles. Hogarth appears to join this critical chorus, casting a cynical perspective on the undertaker’s motives and the worthiness of their services.

In ‘Gin Lane’, Hogarth paints a dire scene of a plagued street where other trades have crumbled, and residents are either incapacitated or on the threshold of death. The undertaker’s prosperity stands starkly against this grim backdrop, profiting off the sorrow and misfortune of others. Hogarth underlines a harsh reality — the undertaker’s profits are born out of other’s losses, drawing parallels with the other thriving businesses on this apocalyptic street; the pawnbroker and the gin shop.

The open coffins and distant funeral procession in ‘Gin Lane’ seem to critique not just the moral but also the aesthetic integrity of the funeral industry. The coffin laid bare is nothing more than a holder for what remains of the stripped-down woman being lowered into it. Yet, its only value seems aesthetic. The funeral procession, though impeccably dressed in mourning outfits, disappears into the background and fails to capture the neighborhood’s attention, suggesting the ineffectiveness of these visual trappings.

Hogarth sharply criticizes the frivolous expenditure on funeral goods that hardly improve the circumstances of the deceased or their grieving kin. Just as residents of ‘Gin Lane’ flirt with ruin in their pursuit of gin, the viewer is warned against squandering money on funerary goods devoid of any practical utility. Here, Hogarth shifts from commenting merely on the gin madness to a larger critique of the way 18th-century Londoners frivolously spent their earnings.