For The First Time In 40 Years, The Federal Government Can Judge Applicants By Merit

In a landmark win for merit-based governance, a federal judge in Washington, D.C. officially terminated the Luevano Consent Decree on Friday, ending a 44-year-old policy that effectively barred the federal government from using standardized tests to evaluate job applicants. The ruling paves the way for President Donald Trump to carry out one of the most transformative reforms to the civil service system in modern American history.

The decree originated in 1981 after Angel Luevano sued the federal government over the Professional and Administrative Career Examination (PACE), a test used to identify top talent among federal job applicants. Luevano claimed the exam disproportionately excluded blacks and Hispanics, and in a final act of surrender, the Carter administration’s Office of Personnel Management (OPM) agreed to halt use of the test for what was supposed to be five years. Instead, the ban remained in place for more than four decades.

That ends now.

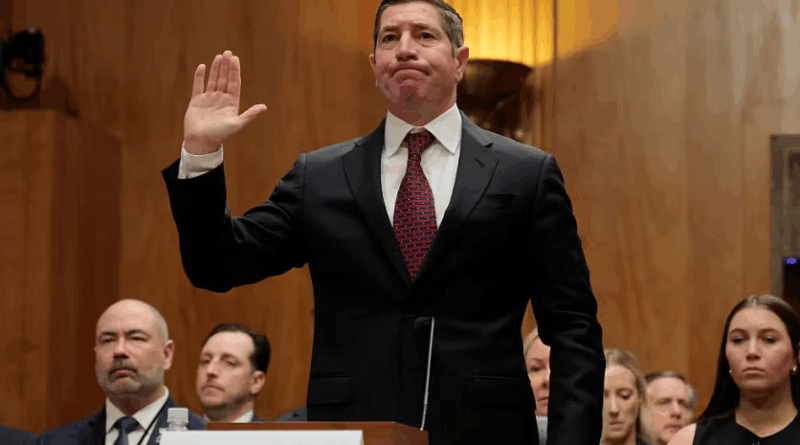

With the support of the original plaintiff, the Trump administration moved earlier this year to reopen the dormant case and formally end the decree. OPM General Counsel Andrew Kloster confirmed there were no concessions made to reach the agreement. “They just flat out agreed,” he said. “It would not have happened without the original named plaintiff agreeing to it and the judge agreeing to accept it.”

The ruling comes as the latest example of Trump’s aggressive push to reform the federal bureaucracy. “We’re making civil service great again,” said OPM Director Scott Kupor, who has spearheaded efforts to reintroduce objective standards into federal hiring. For decades, agencies have relied on so-called “self-assessments” that allowed applicants to rate themselves — often dishonestly — without any verification of their actual skills. The results, Kupor said, have been disastrous for government performance.

With the decree gone, the federal government can now begin designing role-specific assessments that actually test a candidate’s qualifications. For instance, instead of asking a job applicant to describe their proficiency in computer programming, an agency might now administer a coding test. “We’re going to be able to attract really, really good people, because they’re going to be fairly tested for their merit,” Kupor said.

The implications are massive. For the first time in over 40 years, federal hiring managers will be able to evaluate candidates the way private-sector employers do—by testing competence and aptitude, not by checking diversity boxes or relying on unverifiable personal claims.

The Luevano decree was one of the most expansive applications of the controversial “disparate impact” legal theory, which holds that any process that produces unequal racial outcomes must be discriminatory, regardless of intent or fairness. Kloster made it clear that those days are over. “This is really kind of an understanding that disparate impact as a way to measure things is not the law of the land anymore. You have to actually show real discrimination.”

For decades, this policy warped federal hiring in favor of performative equality over actual skill, discouraging innovation, allowing cronyism, and undermining competence. The results were felt by millions of Americans forced to deal with inefficient government agencies staffed by unqualified workers who were nearly impossible to fire.

Now, that culture can begin to change.

“This is a win for fairness, as well as a win for getting American people the ability to get people with the appropriate skills into the right jobs,” Kupor said.

As the Trump administration considers whether to reinstate a general aptitude test or develop job-specific exams across agencies, one thing is certain: the era of unchecked mediocrity in the federal workforce is coming to an end. Merit is back.